This report acknowledges the Spare Vote and make very positive comments about it.

The final report was released by the new Minister of Justice Paul Goldsmith on 16 January 2024.

The main electoral system recommendations from this review report

included:

● Removing the one-seat threshold. This would mean that only

parties passing the party vote threshold could win list seats.

● Lowering the party vote threshold to 3.5%

● Changing the overhang rule to grant overhang seats, and to reduce

the number of list seats by the same amount, so leaving the number of seats unchanged.

● Fix the district/list seat ratio at 60:40 plus one list seat if necessary so as to always have an odd number of seats in parliament

I support the fixing of the 60:40 ratio.

But I fear that the other changes I’ve noted will replace existing problems with new ones.

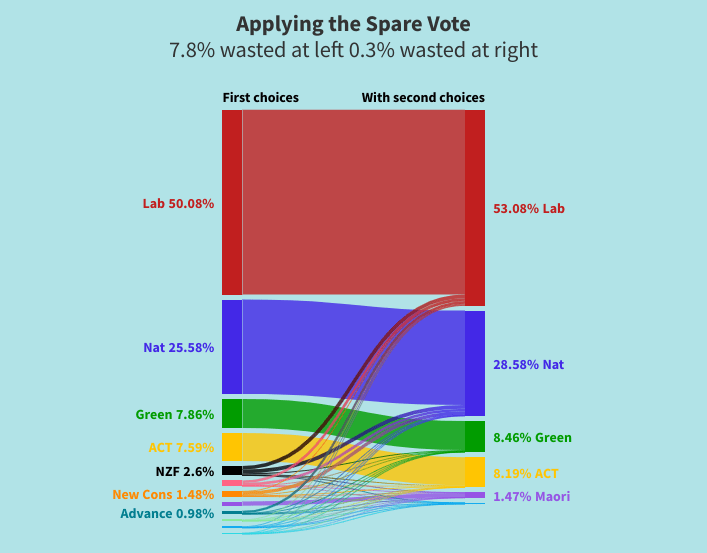

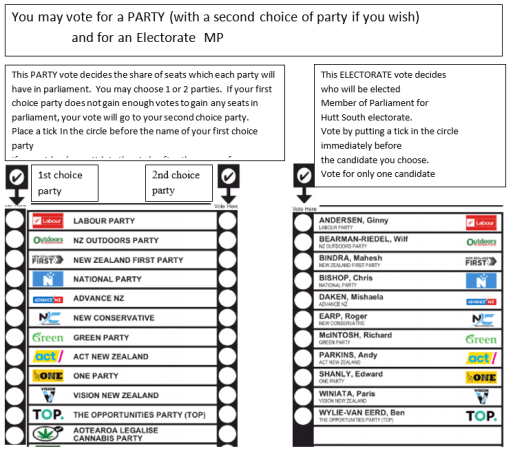

The idea of the spare vote (second choice of party vote) was

acknowledged by the following paragraphs:

4.34 Some submitters advocated strongly for second-choice voting to be introduced for the party vote (that is, an optional “back up” vote for another party if your first choice vote did not pass the threshold), whether the threshold is lowered or not. They differentiated this idea from a full preferential voting system and noted it may improve voter participation rates, support sincere voting rather than tactical voting, reduce the proportion of votes that go to parties that cross neither threshold, reduce barriers for small and newly established parties, and only require a simple change to the ballot paper.

Then later:

4.58 Full preferential voting would allow voters to rank their preferred parties or candidates (for example, they could select a first, second, and third choice). If a voter’s first choice did not succeed, their vote would transfer to their next ranked party or candidate (and so on).

Second-choice voting is an example of partial preferential voting, where voters have the option of selecting a “back-up” party or candidate. Both types of preferential voting could make it easier for smaller parties to get into parliament because voters could support smaller or newly established parties or candidates without fear their vote will not count in the make-up of parliament.

4.59 We acknowledge the strong support these options received from some submitters during consultation, particularly second-choice voting.

However, we remain wary of changes that would complicate the voting process. Adding complexity to how MMP works could be counterproductive, particularly if introduced at the same time as other changes. For these reasons, we think improvements to representation

are better realised by lowering the party vote threshold without adding additional complexity.

I was pleased that the spare vote idea was acknowledged, and that the report notes some of its many advantages.

The final paragraph above was not altogether surprising. The spare vote is an idea that has received little attention so far. I would have been surprised to have a new idea, however good, accepted on the strength of a small number of submissions to a review.

But the report seems very supportive of the idea and the report remarks on the simplicity of the ballot paper changes required. So I feel encouraged.

The report was released by the new Minister of Justice Paul Goldsmith, who stated that some recommendations were already ruled out. These included lowering the voting age to 16 and allowing the vote to all prisoners.

Details at

https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/independent-electoral-review-final-report-released

It will be interesting to see which of the proposed changes garner enough support to be implemented.

Go to https://electoralreview.govt.nz/ for more details.