It seems that there is a problem with many implementations of MMP and similar electoral systems. The problem stems from the use of thresholds to avoid a proliferation of small parties in the representative assembly.

Having a threshold seems innocuous enough, assuming one accepts the premise that it is desirable/important/useful/acceptable to limit the representation of very small parties in parliament.

It seems that most thresholds are implemented in a very simplistic way. If a party does not pass the threshold, it is completely excluded from the assembly. Its votes are discarded. It has no right to have any paid representatives present, to receive any secretarial or office space support, to speak, or to vote.

After discarding the votes of under-threshold parties, seats are allocated generally in proportion to the remaining, qualifying, votes.

Because of this mode of operation, the existence of the threshold creates perverse incentives for almost all players. A vote that was cast for a below-threshold party is a vote taken away from its allied parties and then discarded. Small emerging parties should be well aware that until they pass the threshold, they are working against their allied parties, and against the chances those allied parties have of forming a coalition government after an election. Major parties are not immune from these perverse effects. Major parties need to take into account that apparent support parties, ones of the same side of the left/right divide but below-threshold, are in fact working against the major party’s chances of forming a governing coalition after the election. So an apparent support party is not something to encourage. And it is all made more confusing because nobody can be sure in advance which parties will cross the threshold.

So, not only is the threshold something quite high to overcome, but on the way there all parties are disturbed by the perverse effects of a simple threshold.

So the threshold is about much more than the percentage. It also creates conflicting motivations and loyalties for voters and parties. Voters are torn between voting for a small party and hence against its allied big party OR voting for the allied big party and not for their preferred party. Small parties and their supporters want to encourage voters to support their small party, knowing that they are probably taking votes from the allied big party and wasting them. Big parties fear the negative effects of smaller parties that notionally support them.

That explanation was probably confusing. If so it reflects the confusing and conflicted environment that affects everybody who has connections with small parties in an MMP environment.

But wait there’s more. The MMP party vote does two things. The first thing is to decide which parties are eligible for seats in parliament. The second thing is to measure the relative support of each, and to allocate seats in parliament accordingly. But the voters who voted for under-threshold parties have no say in this allocation. If we are aiming to measure relative support, it seems unfortunate to leave out up to 8% of voters.

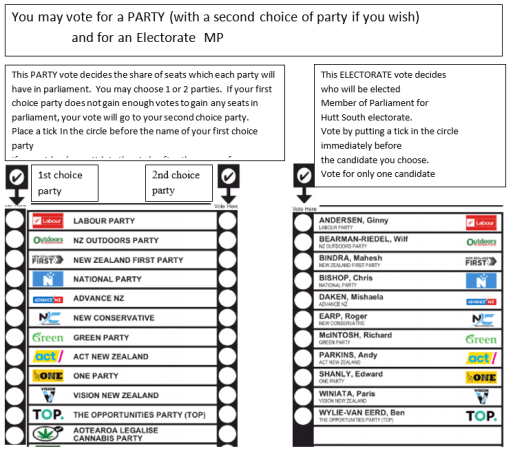

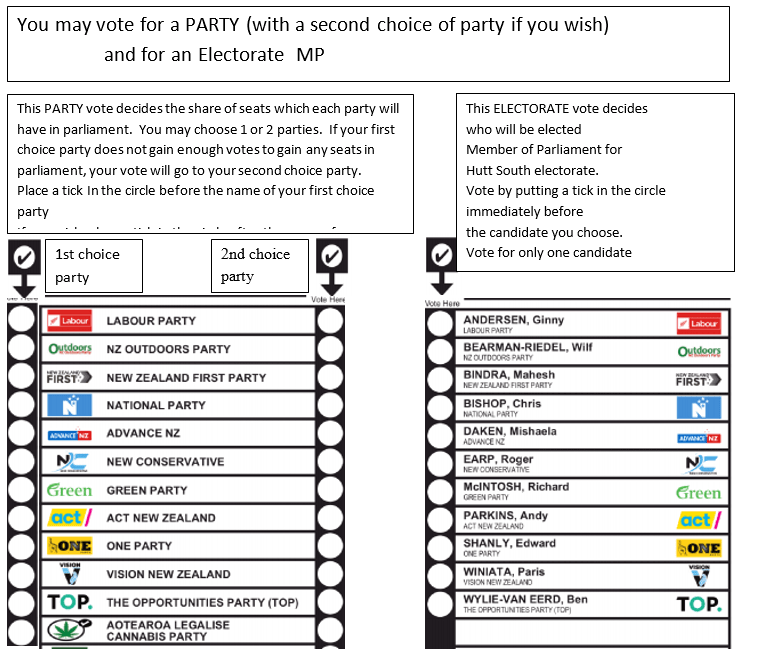

New Zealand’s MMP system uses closed party lists, so the voting paper is very simple. On this voting paper, adding a second column is easy, to allow each voter a second choice of party vote. If a voter’s first choice party falls below the threshold, the vote can go to a second choice. In this way every voter can both nominate a preferred party, and vote for one of the eligible parties.

This second choice eliminates the conflict around small parties and as well allows the party voting to be much more proportional. And the bonus, for those who think the threshold is important, is that these improvements can be made without any change to the threshold percentage.

An advantage of this change is that it should help everybody, so perhaps a consensus is achievable without much delay.

There is of course nothing to prevent the threshold being reduced, but that is another question.

More at www.onthethreshold.nz